Are fixed-effects models sufficient for causal inference?

4 minute read

Photo by Robert Bye on Unsplash

Doing an experiment is by far the gold standard for conducting causal inference research. One common practice, particularly in quantitative social science, is doing randomized control trials (RCTs).

But here’s the scoop: if you’re a young researcher and just starting out, doing RCTs can be super expensive. In fact, for young researchers looking to build their portfolios early in their careers and pave the way for future success, the high expenses associated with RCTs can pose a significant challenge.

Pivoting the Gold Standard

One plausible strategy is they ought to join a legit RA-ship program to get the opportunity of doing RCTs. Otherwise, those who are less lucky should think of an alternative such as conducting quasi-experiment research.

Several methods are available to execute such studies. Popular instances are Difference-in-Difference (Diff-in-Diff), Propensity Score Matching (PSM), Regression Discontinuity Design (RDD), and finally Fixed-Effects (FE).

While the first three methods required specific conditions such as pre-post and treatment-control groups, I personally think that FE is one of the most versatile when it comes to natural experiment design - this opinion may not be correct universally but I think it’s true for most of the cases.

But one major question arises when we prefer this pivot. Is adopting these models sufficient for claiming causal inference?

This article, thus attempts to answer such question by exploring the possible reasonings and cautions in implementing the FE for natural experiment design with panel datasets.

Revisiting FE models

Photo by Bekky Bekks on Unsplash

A. General Setup

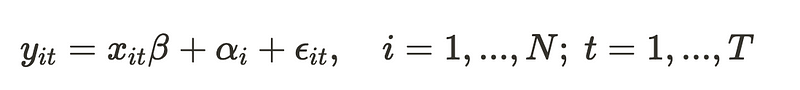

To begin with, let’s check the following general setup for FE model using typical panel datasets:

where y is the expected outcome, predicted by vector covariates x with coefficient β, fixed-effects term α, and error-term ϵ indexed at unit i time t.

B. How FE Models Help Identify Causal Effects?

You’ve probably heard: “Correlation is not causation.” That’s true. But fixed-effects models offer a partial fix - they difference out all unchanging confounders over time.

If you believe that the omitted variables are constant over time (e.g., innate ability, geographic features), the FE transformation eliminates them. This reduces omitted variable bias and brings us closer to estimating the causal effect of x on y.

For example, suppose you’re evaluating the impact of internet rollout on school test scores across districts over a 10-year period. District-level differences in wealth, governance, or culture may bias your results - but if those differences are constant over time, a fixed-effects model accounts for them.

So, FE is valuable - if your theoretical framework justifies it.

C. Beware the pitfalls

FE models sound great. But they’re not a silver bullet. They require strong assumptions, and failing to meet them can lead to misleading conclusions. Below are key issues to watch out for:

Time-Varying Confounders: FE only controls for time-invariant factors. If there are unobserved variables that change over time and also affect both treatment and outcome (e.g., economic policy shifts, shocks, trends), your estimates will still be biased.

Reverse Causality: What if y also affects x? This two-way relationship (endogeneity) is common in social science and violates the assumption of exogeneity. FE models don’t solve this.

Low Within-Unit Variation: FE estimates are identified only from changes within units over time. If your treatment variable doesn’t change much (e.g., a policy that’s adopted once and never changes), you’ll have little identifying variation, and your standard errors may explode.

Measurement Error: Differencing can amplify measurement error, making estimates noisy and biased toward zero.

Bottomline

Here’s a quick decision guide:

✅ Use FE when:

- You have panel data with enough time periods and variation within units.

- You believe time-invariant unobserved heterogeneity is a major concern.

- You suspect confounding, but not by time-varying factors.

❌ Avoid relying solely on FE when:

- Key confounders vary over time.

- Your treatment assignment is endogenous or persistent.

- There’s little variation in treatment within units.

In such cases, you should consider combining FE with:

- Instrumental Variables (IV) for endogeneity

- Event study or dynamic DiD to model pre-trends

- Matching or control function approaches

So, are fixed-effects models sufficient for causal inference? Sometimes - but not always.

FE models are powerful tools, especially when used carefully with rich panel data. But their success in identifying causal effects depends on the assumptions you make and your ability to test them.

A good rule of thumb? Think of FE as a useful method - not a magical one. It’s strongest when supported by a solid theoretical framework, robustness checks, and complementary methods.

This post was written by Ega Kurnia Yazid.

A more detailed technical explanation please check: Fixed effects and Causal Inference

I welcome feedback and constructive criticism. To discuss further you can comment on each post, or you can reach me through any social media platforms you can find on my webpage’s profile.